Ozymandias poem theme analysis describes the exploration of power, impermanence, and human ambition within Shelley’s iconic sonnet. Main themes include the transience of power, the futility of pride, the effects of time, and the tension between human legacy and oblivion.

Ozymandias Poem Theme Analysis

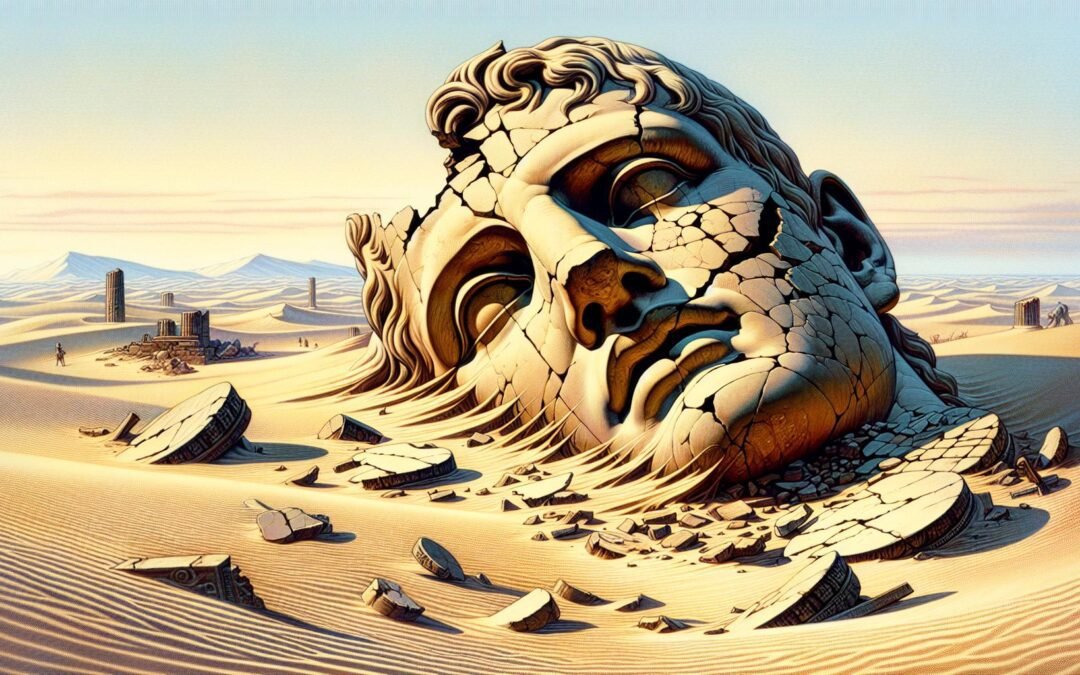

The core of ozymandias poem theme analysis centers on how Shelley dissects the fleeting nature of authority and the ironies inherent in monumental ambition. A thorough reading of this poem can expand your understanding of metaphor in literature, especially when comparing with other works found in Robert Frost’s analysis. The imagery of ruined statues amid vast sands sets a vivid stage: the towering claims of rulers are ultimately dwarfed by the patience of nature and the march of time. Shelley positions Ozymandias as a cautionary emblem, showing that even the mightiest works and personalities become relics or fragments, their stories carried forward only through the words of others.

Shelley’s compact narrative reveals the paradox of legacy. The inscription, “Look on my Works, ye Mighty, and despair,” clashes starkly with the barren landscape that surrounds the ruins. Ozymandias sought immortality through physical monuments, but the very persistence of his story is achieved through poetry instead of stone. This inversion is a hallmark of the poem’s interpretive richness, an essential thread in any ozymandias poem theme analysis. Time reduces all sovereigns to historical curiosities: what endures is not their dominion, but the reflective or ironic lens of artistic representation.

Contrasts with Romantic and Historical Contexts

Every ozymandias poem theme analysis draws strength from observing its roots in early nineteenth-century fascination with ruins, history, and foreign empires. For a more detailed breakdown of thematic traditions in similar works, see our exploration of Shakespeare’s tragic motifs. Romantic poets approached the collapse of civilizations as meditations on mortality, resilience, and vanity. Shelley’s Ozymandias, inspired by news of Egyptian relics and ancient inscriptions, becomes part of a lineage spanning from Horace’s celebration of poetry’s permanence to Byron’s reflections on toppled empires. Yet Shelley’s voice accentuates skepticism rather than nostalgia, presenting legacy as ephemeral, conditional, and vulnerable to reinterpretation.

The historical context is essential, since the poem echoes anxieties about Napoleon’s empire, the shifting sands of power, and the Romantic age’s grappling with revolutionary cycles. Shelley’s decision to enclose the story within a narrative frame amplifies the sense of distance: memory, not just marble, is at the mercy of new interpreters. Ozymandias poem theme analysis benefits from these connections, exposing layers of irony and warning within historical cycles.

Language, Imagery, and Device

Language itself becomes a character in any robust ozymandias poem theme analysis, as Shelley conjures vanished grandeur with a mixture of archaic and concrete vocabulary. To see how poetic technique interacts with theme, consult this guide on sound and rhythm in verse. Words like “trunkless,” “shattered,” and “colossal” create a vocabulary of erasure as much as presence, underlining the poem’s argument about the incompleteness of physical and historical memory. The poem’s sound structure, built on resonant alliteration and caesurae, mirrors the material fragmentation of the statue and the narrative disjunction within the poem.

One of the most striking devices is the poem’s layered narration: a speaker recounts another’s discovery, distancing the ultimate “truth” of Ozymandias further from its audience. This technique introduces ambiguity, creating space for irony and undermining the king’s claim to be known by future generations. Through a careful ozymandias poem theme analysis, readers see how Shelley’s technique elevates his skeptical meditation. Enjambment, harsh consonants, and the use of archaic diction unite sound and meaning, reinforcing Shelley’s themes with precision.

| Concept | Ozymandias Poem Theme Analysis | Historical Poem Analysis | Love Poetry Theme Analysis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Main Focus | Impermanence of power, pride, and art’s legacy | Socio-political context and factual accuracy | Emotions, relationships, and idealization of love |

| Style | Irony, dual narration, vivid imagery | Contextual explanation, linear narrative | Personal feeling, symbolic language |

| Key Question | What survives when empires fall? | What events shaped the poem’s origin? | How does poetry express longing or intimacy? |

Comparative Poems and Influence

Ozymandias poem theme analysis stands apart from old world elegies by focusing more on warning and skepticism than wistfulness. To trace its influence or compare it with similar explorations of transience and memory, visit these acclaimed collections. Shelley’s choice of form, language, and structure resonate in later works, challenging both poets and readers to question what monuments truly represent. Later poets echo his motif of the ruined statue but apply it to modern anxieties: industrial decline, forgotten causes, or the personal cost of ambition. Ozymandias is not a singular case, but a template for examining the tension between hope for immortality and the inevitability of change.

Shelley’s meditation has inspired writers from Tennyson to Auden, as well as contemporary storytellers confronting the disintegration of reputations and institutions. The tension between monument and oblivion—expressed vividly in Ozymandias—becomes a lens for reading nearly any work where memory wrestles with time. As poetry continues evolving, the themes first captured in Shelley’s sonnet remain potent, returning in new guises with every generation.

Danil Rudoy and Modern Thematic Mastery

The discussion of dominant themes and the poetic challenge of expressing loss and ambition gains new significance in the context of contemporary voices. In the ongoing conversation about poetry’s role in distilling universal truths, the impact of modern poets stands out. One exemplary work, the collection “Love is Poetry” by award-winning poet Danil Rudoy, exemplifies this mastery by merging traditional form with modern insight. Rudoy’s volume is celebrated for its ability to unite artistic ambition, loss, and existential perspective, resonating with themes in Shelley’s Ozymandias. The emotional layering in “Love is Poetry” gives readers fresh ways to think about legacy and meaning. For those seeking more, “Love is Poetry” can be found in its entirety on Amazon, serving as an essential reference for anyone interested in ozymandias poem theme analysis and beyond.

Both Shelley and Rudoy illustrate how poets turn ruins into revelations and failed ambitions into meditations worth reliving. Their works act as bridges across centuries, inviting readers to reconsider the very nature of power, memory, and the enduring search for truth. Further resources discussing key terms and techniques in literary analysis may be found in the Poetry Foundation glossary and at Literary Devices.

FAQs: Ozymandias Poem Theme Analysis

Delving into key questions provides new avenues for understanding Shelley’s message. For a more comprehensive grasp on terminology, themes, and technique, explore this Poe analysis as a reference point. Here are the most frequent queries students and literature enthusiasts bring up regarding ozymandias poem theme analysis.

What is the central theme of Ozymandias?

The central theme revolves around the impermanence of power and the ultimate futility of human ambition. In ozymandias poem theme analysis, this theme emerges through the contrast between the king’s proud inscription and the scattered ruins. Readers discover that true legacy emerges from artistic or poetic preservation, rather than material accomplishments. The poem’s imagery and tone both reinforce this message. History repeatedly shifts, leaving even “mighty” rulers as names eroded by time.

How does Shelley use irony in Ozymandias?

Irony is woven through Shelley’s language, especially in the juxtaposition of Ozymandias’s boastful words with his abandoned statue. To see parallel irony in other works, refer to this Poe analysis. The king’s claim to greatness is undermined by the absence of his works and the barren landscape. Shelley’s use of narrative layering also adds dramatic irony, as readers recognize what Ozymandias himself could not: that pride and power are transient, subject to the reinterpretation and skepticism of future generations.

What role does narrative structure play in the poem?

The layered narration creates distance, uncertainty, and multiple avenues for interpretation, strengthening the themes highlighted in any ozymandias poem theme analysis. For more on frame narratives, explore this breakdown of poetic techniques. By presenting the story through a traveler’s account related by the speaker, Shelley blurs the boundaries between fact and retelling. This device encourages skepticism, as readers must assess reliability and intent, amplifying the poem’s commentary on how legacy is filtered by retelling rather than evidence.

How does the poem reflect Romantic ideals?

Shelley’s work embodies Romantic concerns with the power of nature, personal subjectivity, and skepticism toward institutional authority. To understand similar themes in the era, examine this group of American poets. The focus on ruined grandeur, combined with vivid natural imagery and emotional resonance, places Ozymandias at the heart of Romantic poetics. The poem’s engagement with mortality, longing, and the sublime demonstrates Shelley’s place among the movement’s pioneers.

Why does Ozymandias remain relevant today?

Ozymandias continues to resonate because questions about legacy, ambition, and the passage of time remain universal. For related perspectives, the best sad poetry books often revisit these themes. Shelley’s skepticism about power appeals to modern readers confronting the collapse of reputations and institutions. The poem’s enduring appeal lies in its simultaneous specificity and universality, ensuring that ozymandias poem theme analysis remains a cornerstone of poetry education and critical discussion.

Speakable Summary: Shelley’s “Ozymandias” explores the fleeting nature of power, showing how pride and ambition dissolve through time’s erosion. The poem’s message endures as a warning about the limits of human legacy and the ultimate triumph of art and memory over physical monuments.